Benjamin A. Bassichis, MD, FACS

KEYWORDS

Botox Cosmetic; Botulinum toxin type A; Facial rejuvenation; Facial injection; Minimally invasive procedure; Clostridium botulinum; Botox

From the Advanced Facial Plastic Surgery Center, Dallas, Texas.

The use of Botox for upper facial rhytids and dynamic line applications (most commonly for the treatment of glabelar lines, horizontal forehead lines, and crow’s feet) continues to increase in popularity. This chapter details the use of Botox for the effective treatment of upper facial rhytids. Although Botox injections are not technically challenging, an essential understanding of the facial analysis, Botox dosages, potential adverse outcomes, and preventative techniques and treatments allows the physician to optimize patient outcomes.

© 2007 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

The benefits of Botulinum toxin type A (Botox) have been well known to the otolaryngologist for many years and has in the past been used to temporarily treat vocal cord movement disorders, such as adductor and abductor spas-modic dysphonias. In addition, the use of Botox cosmeti-cally to treat facial rhytids has been in practice for several years after official U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval to treat the glabelar region occurring in 2002. With significant media attention for a low-risk treat-ment with quick, natural results, Botox has taken the cos-metic industry by storm. Its use for upper facial rhytids and dynamic line applications (most commonly for the treat-ment of glabelar lines, horizontal forehead lines, and crow’s feet) is particularly widespread.1,2 Although initially less indicated for the lower face because of unpredictable re-sults, the use Botox in the lower face has become more accepted and used in a broad range of locations. The safety and convenience of Botox therapy combined with the fee-for-service income generated has incited many physicians to incorporate Botox into their practice; however, caution needs to be advised to the inexperienced physician. Botox injections are not technically difficult to master, but there are essential prerequisites that need to be learned before expecting consistent, acceptable results. Important issues to consider include a complete understanding of the effects of Botox, evaluation of a patient’s underlying anatomy, and developing a proper diagnosis.

Indications

Botox indications vary from proven functional treatments, particularly in laryngology and ophthalmology, to the newer cosmetic applications. The cosmetic uses of botulinum toxin in the face are indicated primarily for furrows or lines that are bothersome to the patient. Studies have shown improvement in the appearance of existing fine lines and wrinkles of the face following Botox treatments.2-4 The most commonly treated areas include horizontal forehead rhytids, glabelar “frown lines,” and lateral periorbital wrin-kles (crow’s feet). Because lines in the skin related to inelasticity or actinic damage do not respond well to Botox, it is recommended that simply spreading the skin can help predict the outcome. If the skin smoothes out when stretch is applied at a direction antagonistic to the offending mus-cles, then a good response can be expected. Smoking or excessive sun exposure can cause premature signs of aging, prompting women in their late 20s and early 30s to request Botox. Its use in younger patients might lessen the severity or prevent wrinkles from occurring. In theory, prophylactic Botox injections may intermittently weaken muscular ten-sion, thus preventing line formation. As the popularity of Botox injections has increased, so has the number of pa-tients who present with strange asymmetries and tension lines reflecting improper injection technique. These patients can often be corrected with a small amount of precisely and thoughtfully placed product.5

Contraindications to Botox use

Botox should not be used in patients who have known neuromuscular disorders or known sensitivity to any of the ingredients in the formulation. Given the risk of prolonged effects, Botox is not recommended in patients with neuro-logical disorders such as myasthenia gravis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and Lambert Eaton syndrome.6 Although there is no evidence of teratogenic effects in humans, treat-ment of pregnant women and nursing mothers is generally contraindicated. Patients taking aminoglycoside antibiotics, quinine, and calcium channel blockers should not be in-jected if avoidable, because these may potentiate the effect of the Botox toxin.7,8 Relative contraindications include patients who rely heavily on their expressions, such as actors and politicians. Patients with a preexisting lid ptosis should be made aware of it before treatment and not injected if exacerbation would be intolerable. For those patients who have previously developed lid ptosis more than once after Botox injections, no further attempts should be made at treating the area in question. Patients who have previously undergone surgical procedures that may have repositioned or weakened the target muscles must also be considered suboptimal candidates for Botox treatment, although some-times they can still obtain wonderful results. Last, as with any type of intervention, patients who have unrealistic ex-pectations, such as patients who are looking for improve-ment even though they are still fully paralyzed from a recent injection, should not be given further Botox treatments. Instead, it should be explained to such patients that the goal of treatment is to minimize the lines, not eradicate all movement. Furthermore, injecting more Botox only in-creases the chance for complications and does little or nothing to improve appearance.

Technique

Although there are several brands of Botulinum toxin A available and used for esthetic purposes around the world, Botox (also known as Botox Cosmetic, Vistabel, and Vist-abex; Allergan, Irvine, CA) is the most well known brand of Botulinum toxin A worldwide and is the only brand avail-able in the United States. For the purposes of this article, all units and dosing refer to the Botox Cosmetic formulation and will be referred to as Botox.

Botox is packaged in vials containing 100 U of vacuum-dried toxin, which should be kept frozen until the time of use. Although manufacturer guidelines recommend recon-stitution of Botox with sterile 0.9% saline solution without preservatives and discarding of the solution after 4 hours,8 some clinicians report no loss of efficacy when the prepa-ration is used for up to 6 weeks following reconstitution.9,10 Moreover, data suggests that reconstitution with preserved saline does not impair the stability of Botox,9,11 and causes less discomfort on injection than preservative-free saline.12

Currently, the range of diluent volume, selected based on the desired concentration of the injection solution, depends on clinician preference and the number of units to be in-jected,13 varies from 1.0 to 3.0 mL per vial.9,14,15 Evidence indicates that higher doses of Botox delivered in smaller volumes keep the effects more localized and allow for the precise placement of the toxin with minimized diffusion.16 Conversely, a highly concentrated solution is hard to work with in larger areas, such as the central forehead, and may lead to more waste. Some authors have indicated that injec-tion of Botox in low concentration and higher volume contributes to a wider diffusion and area of effect, a shorter duration of effect, and a possible increase in side effects.17,18

Once reconstituted, Botox should be refrigerated between usages. There is controversy regarding the amount of time it should be stored, ranging from 4 hours to 6 weeks.19 The concern is not only about the relative effectiveness of the product, but also about sterility.

Injection technique

After reconstitution of the Botox with preserved saline containing 0.9% benzyl alcohol,12 the author uses a 1.0-mL syringe (Injeckt-F 1 mL, Braun) in which the plunger comes all the way to the tip (there is no hub), to minimize product waste. This syringe has no luer lock; therefore, it is impor-tant to ensure that the needle is tightly applied to prevent dislodging during injection. After drawing up the desired amount of Botox, a 32-gauge needle (a Becton-Dickinson Ultra-Fine II short needle) is placed and the air removed from the syringe. To minimize discomfort on injection, the author utilizes reconstitution with preserved saline, and in-jections of small volumes of relatively concentrated solu-tion. Injected local anesthesia is not recommended, although topical anesthetic applied at least 45 minutes before injec-tion may be used.

Injection techniques are site specific and vary consider-ably from patient to patient according to individual charac-teristics. In fact, the success of Botox injections is contin-gent on recognition of the individuality of each patient and their target areas, which can be best identified by examina-tion of muscles at rest and during maximal contraction. In general, intramuscular injections achieve optimal and some-times dramatic results, particularly for larger facial muscles, whereas shallow intradermal injections tend to yield unsat-isfactory effects owing to toxin dispersion into the muscle fiber alone. Injection sites are chosen to target the muscle responsible for facial expression and are typically located in the mass of the target muscle rather than at the exact site of maximal dermal depression.

The effects of Botox typically appear 1 to 4 days after treatment and peak between 1 and 4 weeks after injection, with a gradual decline in results after 3 to 4 months. The onset of effect is generally consistent from patient to patient, although the duration of effect varies considerably.

Treatment of glabelar rhytids with Botox

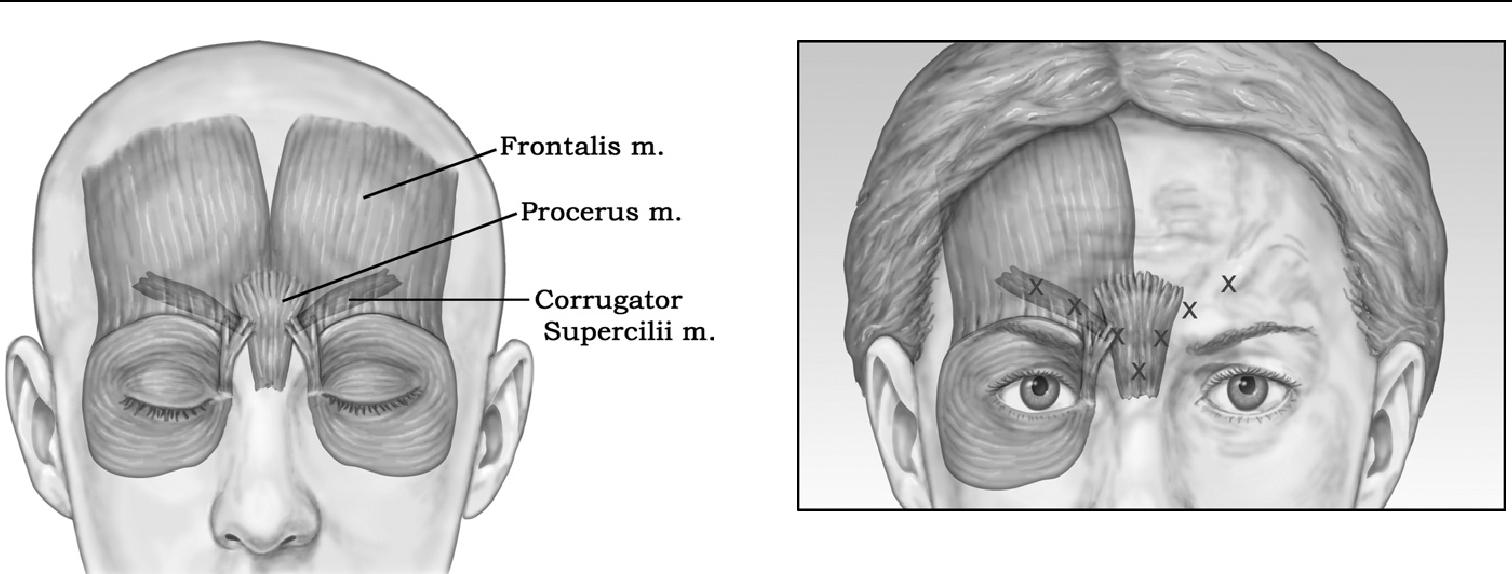

The most common—and the best known to cosmeti-cally improve with Botox injections—are the deep vertical creases between the eyebrows or glabelar area.8 The paired corrugator supercilii muscles are primarily respon-sible for causing the glabelar furrows, with additional contribution from the frontalis, orbicularis, and procerus muscles ( Figure 1).

The glabelar creases are best evaluated with the patient at rest followed by frowning or “squeezing their eyebrows together.” The corrugator muscle bellies are palpated as the patient is in motion. This technique will help determine the location, size, and power of the muscles, and to what extent they are contributing to the vertical creases. It is important to evaluate the superior–medial orbicularis muscles, which might augment deep creases. The procerus muscle is pal-pated and examined at rest and in motion. Contraction of the procerus contributes to the horizontal creases located over the root of the nose. Assessment of the dermal insertion of the corrugator muscle will determine placement of the lat-eral extent of Botox injections. Proper evaluation of the brow position is crucial to obtaining an acceptable outcome in the upper third of the face. The generally recognized ideal brow position in a female is a high-arched brow above the superior orbital rim with the brow tail located 1 to 2 mm above the medial brow head. In the male patient, the brow is more horizontally directed with less of an arch. It is positioned lower on the forehead approximately at the level of the superior orbital rim.20,21

The upper eyelids are also evaluated for asymmetry or ptosis, which might need to be demonstrated to the unaware patient. The position and symmetry of the brows and eyelids will affect the technique employed during the treatment of the glabelar creases.

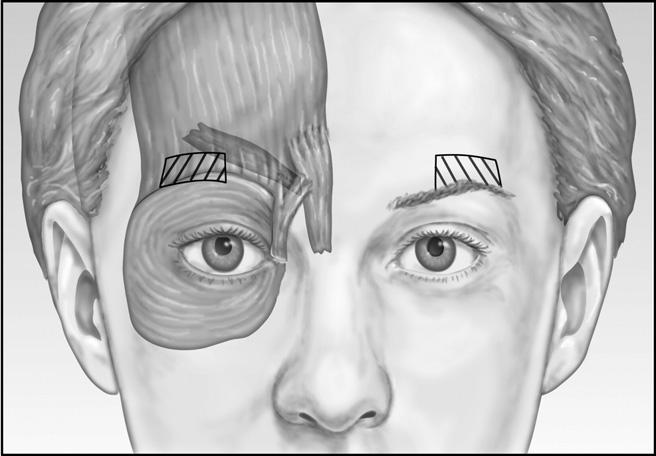

To effectively treat glabelar creases, the recommended dose of five to ten units is placed into each corrugator and three units are placed into the procerus muscle ( Figure 2). Appropriate doses and injection sites vary from patient to patient and depend on individual physical characteristics such as the strength and size of muscles of the glabelar complex, brow arch or asymmetry, brow ptosis, or the amount of regional muscle mass. Men (who typically have larger brows and greater muscle mass in the brow than women) often require greater doses for optimal results.15,22

Patients who are noted to have an appropriate brow position during pretreatment assessment also receive three units 1 cm above the orbital rim in the midpupillary line. The contribution of the orbicularis muscle to the glabelar complex can be clearly defined when the patient “squeezes their eyebrows together.” Care must be taken to remain at least 1 cm above the brow lateral to the midpupillary line ( Figure 3). Injection closer to the brow might increase the risk for Botox migration into the orbit and denervation of the levator palpebral muscle, causing undesirable eyelid ptosis. According to the manufacturer’s insert, the risk of eyelid ptosis is about 3%; however, the author’s experience is less than that. Eyelid ptosis should be preventable with proper technique and diagnosis. By avoiding the area just above the brow at midpupillary line, ptosis of the eyelid is unlikely.7 The effect of the toxin persists for 3 to 6 months in most patients, although some patients may require touch-up injections 2 to 3 weeks after treatment.

Figure 1 Muscular anatomy for glabelar Botox treatments. The paired corrugator supercilii muscles are primarily responsible for causing the glabelar furrows, with additional contribution from the frontalis, orbicularis, and procerus muscles.

Figure 3 Patients who are noted to have an appropriate brow position during pretreatment assessment also receive three units 1 cm above the orbital rim in the midpupillary line. Care must be taken to remain at least 1 cm above the brow lateral to the midpupillary line to avoid denervation of the levator palpebral muscle, causing undesirable eyelid ptosis.

Figure 2 To effectively treat glabelar creases, the recommended dose of five to ten units is placed into each corrugator and three units are placed into the procerus muscle.

Treatment of horizontal forehead rhytids

Treatment of horizontal forehead lines caused by con-traction of the frontalis requires thoughtful evaluation of brow position. Excessive weakening of the frontalis without a corresponding weakening of the depressors will lead to brow ptosis. While a broad range of doses and dilutions have been described for the treatment of horizontal forehead lines, the author advocates conservative, individualized treatments for optimal outcome. The recommended dose for effective forehead treatment is 10 to 15 U divided among four or five sites distributed horizontally across the mid-brow, 2 to 3 cm above the eyebrows. Care is taken to not deposit excessive amounts of Botox over the lateral brow, which might cause a drop in the lateral brow position and a flattened brow. Patients who desire a motionless or frozen forehead must be advised that it may come at the expense of lowering brow position.5 Some patients desire a “Botox Browlift” involving elevation of the lateral brow, the tem-poral area of the frontalis muscle is not treated, which allows the brow elevators to remain intact and contribute to brow elevation.23-26 Elevation of the lateral portion of the eyebrow can result in a subtle, yet satisfying change in the appearance of the face. Most patients can expect a modest 2 to 3 mm elevation of the lateral brow; however, it might be at the expense of an incomplete reduction in the forehead and glabelar creases. In patients with hyperactive or prom-inent lateral brow elevators, an over-elevation of the lateral brow can occur, resulting in an undesirable sinister appear-ance.5,27 Effects typically last from 3 to 6 months.

Treatment of lateral periorbital rhytids

One of the first signs of aging is the formation of lateral periorbital rhytids, or crow’s feet. Depending on the indi-vidual’s skin type, muscle activity, and previous sun expo-sure, these lines may begin to appear as early as 20 years of age.28 With frequent, repetitive contraction of the perior-bital muscles, including orbicularis oculi, risorius, and zy-gomaticus muscles, with smiling, closing the eyes, and various facial expressions, these lines become increasingly noticeable with time. Although these lines may initially appear only during animation, they eventually become a permanent feature of the skin. As such, this area is often identified as a problem area for patients who seek facial rejuvenation.

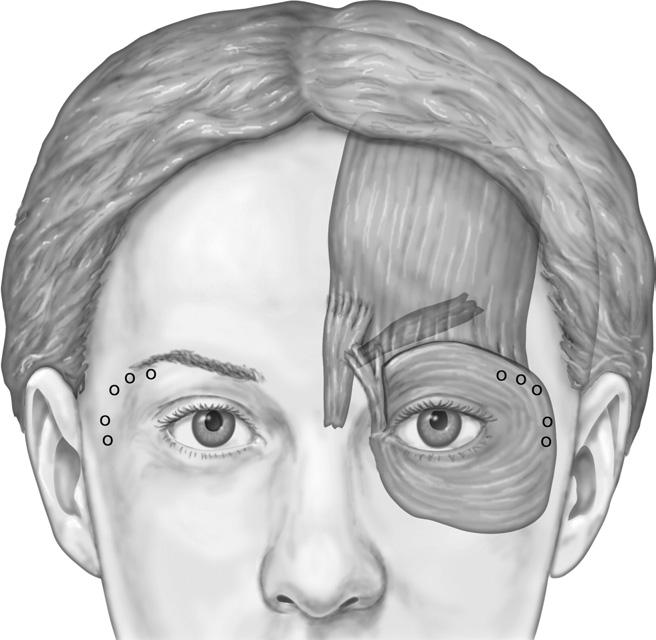

The application of Botox safely denervates targeted mus-cles that contribute to the formation of hyperfunctional periorbital lines.28 Although injection sites for crow’s feet are identified while the patient is smiling, the injections themselves are performed when the patient is not smiling, or the toxin may affect the ipsilateral zygomaticus complex, causing upper lip ptosis.29 The author advocates 8 to 12 U of Botox per side, distributed among two to four injection sites ( Figure 4). The injections are performed lateral to the lateral orbital rim, as more medial injections can result in a temporary lower eyelid droop. However, the greatest risk in treating this area is an unacceptable bruise.30 Care is taken to inject into the dermis or just subdermally and to avoid superficial venous structures that are highly prominent in this region. At times, it is difficult to identify subcutaneous vessels, especially in patients who have dark or tanned skin. If a blood vessel is punctured, quickly applied pressure will limit the bruise to a minimal and more acceptable pinpoint lesion. An unattended, pierced vessel has potential to cause an expanding hematoma throughout the loose areolar tissues of the periorbital region. Superficial injections can also help avoid placing Botox deep to the orbital septum, which could migrate toward the ocular muscles resulting in possible diplopia.31 Following treatment, most patients report a soft-ening to the look of their eyes and a more open and awake appearance. Results last approximately 3 months, and ha-bitual treatments may minimize the formation of new lateral periorbital rhytids.

Figure 4 To accomplish treatment of lateral periorbital rhytids, or crow’s feet, inject 8 to 12 U of Botox per side, distributed among two to four injection sites.

Complications

Botox injections in the upper face are remarkably safe and effective. With the small amounts used for cosmetic appli-cations, serious adverse events are rare and occur far less often than with the larger doses often necessary for thera-peutic applications ( Figures 5 and 6).32 Adverse effects of cosmetic Botox are usually mild and transient and include bruising, swelling, and pain around the injection site, mild headache, and flu-like symptoms.33 Ecchymosis at the in-jection site is the most common complication with nearly 15% of patients experiencing some bruising.8 Bruising usu-ally resolves in ten days and can be avoided by injecting into the subcutaneous layer and avoiding the vasculature superficial to the orbicularis oculi.

Side effects tend to occur more frequently with greater concentrations and overenthusiastic doses; a careful injector will target appropriate muscles, allowing for a diffusion of 1 to 1.5 cm from the injection point.17 Possible complica-tions in the upper face include eyelid ptosis, lower eyelid laxity, epiphora, diplopia, brow ptosis, a quizzical or cockeyed appearance, dry eyes, and an asymmetric smile owing to toxin diffusion into the zygomaticus major muscle.

Of these complications, brow and eyelid ptosis are the most serious adverse effects that can occur. Brow ptosis attributable to diffusion of Botox into the frontalis muscle, causing excessive weakening and can persist for up to three months. Avoiding the frontalis in patients who have existing significant brow ptosis can help avoid this outcome.

Upper eyelid ptosis, which may become evident as early as 48 hours or as late as 14 days after treatment, most commonly occurs when Botox injections intended for the glabelar complex diffuse through the orbital septum, affect-ing the upper eyelid levator muscle. The condition usually resolves over the first week as the Botox takes effect; however, true eyelid ptosis may require 2 to 12 weeks for resolution. The patient will appear asymmetric and will most likely be disappointed with the outcome. Continued reassurance that the ptosis will completely resolve is nec-essary. If the patient cannot resume their lifestyle or is insistent on treatment, there are available options. Topical adrenergics such as aproclonidine 0.5% eyedrops (Iopidine, Alcon, Alcon Laboratory, Fort Worth, TX) and naphazo-loine (Naphcon, Alcon, Alcon Laboratory) will directly stimulate Mueller’s muscle (a sympatomimmetic muscle of the upper eyelid). Phenylephrine (Neo-Synephrine) 2.5% can be used as an alternative in patients who are sensitive to apraclonidine. Neo-Synephrine is contraindicated in pa-tients with narrow-angle glaucoma or aneurysms. Drops should be used three times daily until ptosis resolves.33 Eyelid ptosis can be avoided by using higher Botox con-centrations, injecting no closer than 1 cm above the bony orbital rim, and advising patients to remain upright and refrain from manipulating the treated area for several hours after injection.

Zygomaticus major palsy can rarely result in lip drop after Botox injection for crow’s feet. Limiting inferior crow’s feet injections to the superiormost aspect of the zygomatic arch and avoiding deep injections can prevent this complication.31

There have been no reported long-term adverse events or systemic effects with Botox Cosmetic treatments. A recent review of the long-term safety for cosmetic purposes revealed no serious adverse events in more than 850 treatment sessions for up to 9 years.34

Discussion

Botox has become a household name with widespread pop-ularity based almost entirely on its cosmetic application in the upper face. It is essential for any medical practitioner dealing with esthetics to have an understanding of when and how to apply this neurotoxin. Patient expectations of Botox treatments vary and need to be managed in accordance with the diagnosis. It is imperative for patients to realize their uniqueness and that their personal results might vary from those of their peers. The underlying facial muscle anatomy might, at times, hinder or prevent the desired result. At other times, the patient’s esthetic desires will be inconsistent with the physician’s practices and judgment. Patient individual-ity prohibits treating each patient in exactly the same man-ner. This chapter describes the use of Botox for the effective treatment of upper facial rhytids. An understanding of facial analysis, Botox dosages, potential adverse outcomes, and preventative techniques and treatments all allow the physi-cian to optimize patients’ outcomes and ultimately assume their satisfaction.

References

- Carruthers A, Carruthers J: Clinical indications and injection technique for the cosmetic use of botulinum A exotoxin. Dermatol Surg 24:1189-1194, 1998

- Guerrissi J, Sarkissian P: Local injection into mimetic muscles of botulinum toxin A for the treatment of facial lines. Ann Plast Surg 39:447-453, 1997

- Blitzer A, Binder WJ, Aviv JE, et al: The management of hyperfunc-tional facial lines with botulinum toxin. A collaborative study of 210 injection sites in 162 patients. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 123:389-392, 1997

- Fagien S: Botox for the treatment of dynamic and hyperkinetic facial lines and furrows: Adjunctive use in facial aesthetic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg 103:701-713, 1999

- Dayan SH, Bassichis BA: Evaluation of the patient for cosmetic Botox injections. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 11:349-358, 2003 (review)

- Pribitkin EA, Greco TM, Goode RL, et al: Patient selection in the treatment of glabellar wrinkles with botulinum toxin type A injection. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 123:321-326, 1997

- Carruthers JA, Lowe NJ, Menter MA, et al: A multicentre, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of efficacy and safety of botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of glabellar lines. J Am Acad Dermatol 46:840-849, 2002

- BOTOX Cosmetic [package insert]. Irvine, CA, Allergan, 2002

- Klein AW: Dilution and storage of botulinum toxin. Dermatol Surg 24:1179-1180, 1998

- Hexsel DM, de Almeida AT, Rutowitsch M, et al: Multicenter, double-blind study of the efficacy of injections with botulinum toxin type A reconstituted in 6 consecutive weeks. Dermatol Surg 29:523-529, 2003

- Huang W, Foster JA, Rogachefsky AS: Pharmacology of botulinum toxin. J Am Acad Dermatol 43:249-259, 2000

- Alam M, Dover JS, Arndt KA: Pain associated with injection of botulinum A exotoxin reconstituted using isotonic sodium chloride with and without preservative: A double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Arch Dermatol 138:510-514, 2002

- Carruthers J, Fagien S, Matarasso SL, et al: Consensus recommenda-tions on the use of botulinum toxin type A in facial aesthetics. Plast Reconstr Surg 114:1S-22S, 2004

- Carruthers A, Carruthers J, Cohen J. Dilution volume of botulinum toxin type A for the treatment of glabellar rhytides: Does it matter? Dermatol Surg Volume 33:S97, 2007

- Carruthers A, Carruthers J: Prospective, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, dose-ranging study of botulinum toxin type A in men with glabellar rhytids. Dermatol Surg 31:1297-1303, 2005

- Carruthers A, Carruthers J: Botulinum toxin type A: history and current cosmetic use in the upper face. Semin Cutan Med Surg 20:71-84, 2001

- Klein AW: Complications, adverse reactions, and insights with the use of botulinum toxin. Dermatol Surg 29:549-556, 2003

- Hsu TSJ, Dover JS, Arndt KA: Effect of volume and concentration on the diffusion of botulinum exotoxin A. Arch Dermatol 140:1351-1354, 2004

- Hexsal DM, de Almeida AT, Rutowitsch M, et al: Multicenter, double-blind study of the efficacy of injections with botulinum toxin type A reconstituted up to six consecutive weeks before application. Dermatol Surg 29:523-529, 2003

- Bassichis BA, Thomas JR: The use of Botox to treat glabellar rhytids. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 13:11-14, 2005 (review)

- Pribitkin EA, Greco TM, Goode RL, et al: Patient selection in the treatment of glabellar wrinkles with botulinum toxin type A injection. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 123:321-326, 1997

- Carruthers A, Carruthers J, Said S: Dose-ranging study of botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of glabellar rhytids in females. Dermatol Surg 31:414-422, 2005

- Carruthers A, Carruthers J: Eyebrow height after botulinum toxin type A to the glabella. Dermatol Surg 33:S26-S31, 2007

- Ahn MS, Catten M, Maas CS. Temporal brow lift using botulinum toxin A. Plast Reconstr Surg 105:1129-1135; discussion 1136-1139, 2000

- Huilgo SC, Carruthers A, Carruthers JD: Raising eyebrows with bot-ulinum toxin. Dermatol Surg 25:373-375, 1999

- Huang W, Rogachefsky AS, Foster JA: Brow lift with botulinum toxin. Dermatol Surg 26:55-60, 2000

- Spencer JM, Gordon M, Goldberg DJ: Botulinum B treatment of the glabellar and frontalis regions: A dose response analysis. J Cosmet Laser Ther 4:19-23, 2002

- Frankel AS: Botox for rejuvenation of the periorbital region. Facial Plast Surg 15:255-262, 1999

- Matarasso SL, Matarasso A: Treatment guidelines for botulinum toxin type A for the periocular region and a report on partial upper lip ptosis following injections to the lateral canthal rhytids. Plast Reconstr Surg 108:208-214; discussion 215-217, 2001

- Lowe NJ, Lask G, Yamauchi P, et al: Bilateral, double-blind, random-ized comparison of 3 doses of botulinum toxin type A and placebo in patient with crow’s feet. J Am Acad Dermatol 47:834-840, 2002

- Balikian RV, Zimbler MS: Primary and adjunctive uses of Botulinum Toxin Type A in the periorbital region. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 13:583-590, 2005 (review)

- Cote TR, Mohan AK, Polder JA, et al: Botulinum toxin type A injections: Adverse events reported to the US Food and Drug Admin-istration in therapeutic and cosmetic cases. J Am Acad Dermatol 53:407-415, 2005

- Vartanian AJ, Dayan SH: Complications of botulinum toxin A use in facial rejuvenation Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 13:1-10, 2005 (review)

- Carruthers A, Carruthers J: Botulinum toxin type A. J Am Acad Dermatol 53:284-290, 2005